|

-

General

Asset Protection Guidebook

As asset protection tools, the limited partnerships really reign supreme. The single greatest proclamation in recent years to my own estate planning clients, is that the limited partnership is without peer in the asset protection area. See Oshins, supra, at p. 43; Mitton, “Asset Protection Guidebook,” p. 13 (1992).

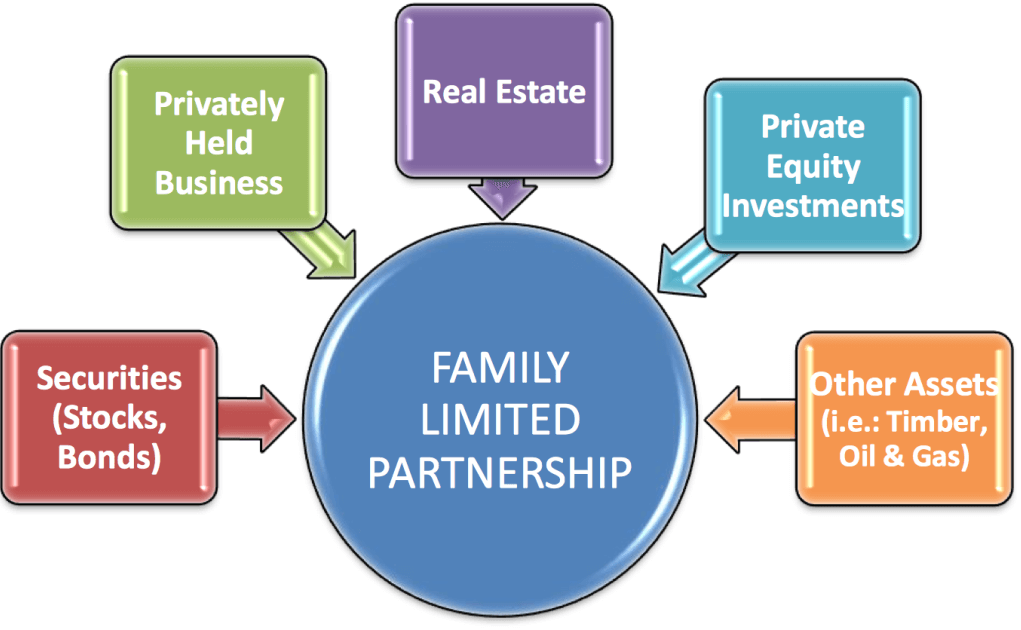

In addition to the typical benefits of a family limited partnership for income and estate tax purposes (e.g., shifting income to family members in lower brackets, creation of fractional discounts, maintaining control and management, and simplifying annual exclusion and other gifting) a major benefit of a family limited partnership is that if a family member is unable to satisfy a creditor, that creditor’s only remedy may be to receive a “charging order” against that family member’s partnership interest. Unless there has been a fraudulent conveyance to the partnership, the creditor cannot reach the partnership’s assets.

There has been much interest in Family Limited Partnerships recently as reflected by the number of articles appearing on this topic, some of which include: Tucker and Mancini, “Family Limited Partnerships and Asset Protection” 23 Journal of Real Estate Tax 183 (Spring, 1996); Willms, “Drafting Tips to Obtain Maximum Tax Savings From Family Limited Partnerships” 24 Taxation for Lawyers 196 (January/February, 1996); Weiner and Leipzig, “Family limited Partnerships Can Leverage the Annual Exclusion and Unified Credit” 82 Journal of Taxation 164 (March, 1995); Jones, “Family Limited Partnerships Achieve Tax and Non-Tax Goals” 23 Taxation for Lawyers (January/February, 1995); Mulligan and Braly, “Family Limited Partnerships Can Create Discounts” Vol. 21 No. 4 Estate Planning (July/August, 1994); Henkel, “How Family Limited Partnerships Can Protect Assets” 20 Estate Planning 3 (January/February, 1993); and Soloman and Saret “Asset Protection Strategies: Tax and Legal Strategies,” Wiley Law Publications (1993).

There has been much interest in Family Limited Partnerships recently as reflected by the number of articles appearing on this topic, some of which include: Tucker and Mancini, “Family Limited Partnerships and Asset Protection” 23 Journal of Real Estate Tax 183 (Spring, 1996); Willms, “Drafting Tips to Obtain Maximum Tax Savings From Family Limited Partnerships” 24 Taxation for Lawyers 196 (January/February, 1996); Weiner and Leipzig, “Family limited Partnerships Can Leverage the Annual Exclusion and Unified Credit” 82 Journal of Taxation 164 (March, 1995); Jones, “Family Limited Partnerships Achieve Tax and Non-Tax Goals” 23 Taxation for Lawyers (January/February, 1995); Mulligan and Braly, “Family Limited Partnerships Can Create Discounts” Vol. 21 No. 4 Estate Planning (July/August, 1994); Henkel, “How Family Limited Partnerships Can Protect Assets” 20 Estate Planning 3 (January/February, 1993); and Soloman and Saret “Asset Protection Strategies: Tax and Legal Strategies,” Wiley Law Publications (1993).

-

Creditors Are Generally Limited to Charging Orders

One of the primary reasons for the use of family limited partnerships as an asset protection technique is that creditors of an individual partner in the partnership cannot attach or levy upon the property of the partnership, unless the partnership also happens to be liable on the obligation in question. Rather, creditors have been limited to obtaining a “charging order” against the debtor-partner’s interest in the partnership. See Atlantic Mobile Homes, Inc. v. LeFever, 481 So.2d 1002 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1986). Section 620.153 of the Florida Statutes provides, in part, as follows:

On application to a court of competent jurisdiction by any judgment creditor of a partner, the court may charge the partnership interest of the partner with payment of the unsatisfied amount of the judgment with interest. To the extent so charged, the judgment creditor has only the rights of an assignee of the partnership interest.

In Atlantic Mobile Homes, the court recognized that it would be inappropriate to liquidate a partnership to satisfy claims sought against an individual partner debtor. See also In re Stocks, 110 B.R. 65 (Bkrtcy. N.D. Fla. 1989), which held that a charging order obtained by a judgment creditor against a debtor’s limited partnership interest only entitles the creditor to the rights of an assignee of the partnership interest; namely, to share in the profits and surplus of the partnership, not to exercise the rights or powers of a partner (so as to prevent disruption of the partnership business).

See, however, Crocker Nat’l. Bank v. Perroton, 208 Cal. App. 3d 1 (1989), in which the Court of Appeals of California addressed the question whether a charged limited partnership interest was subject to foreclosure and sale. It was held that a court can authorize a sale of a debtor’s partnership interest where (1) the creditor had a charging order, (2) all partners other than the debtor agree to the sale, and (3) the judgment remained unsatisfied.

See, also Hellman v. Anderson, 233 Cal. App. 3d 840 (1991), in which the court held that a judgment debtor’s interest in a general partnership may be foreclosed upon and sold, even if the other partners do not agree, provided the sale does not unduly interfere with the partnership’s business.

Finally, see Schiller v. Schiller, 625 So 2d 856 (Fla. Dist. Ct. App. 1993), in which the Fifth District Court of Appeals of Florida held that a court may enforce a charging lien by sale of a general partnership interest and the purchaser of such interest may ultimately apply for dissolution of the partnership whereupon the assets of the partnership can be reached. It should be noted that the foregoing remedy of dissolution may only be applicable to general partnerships given the court’s reliance on Fla. Stat. § 620.715 (2) which is peculiar to the General Partnership Act.

-

Creditors May Have Adverse Income Tax Consequences From Charging Order

Some tax commentators believe that a judgment creditor must pay income taxes on the profits and income attributable to a partnership interest over which he holds a charging order even if no income is distributed by the partnership, based upon Rev. Rul. 77-137, 1977-1 C.B. 178. The exposure to potential income tax by a creditor on phantom income has been referred to as the “KO by the K-1.” See Oshins, supra, and Mitton, supra. Oftentimes it may be possible for the general partner of a family limited partnership to delay distributions to its partners and also take a reasonable salary for its services. It is possible for a creditor with a charging order to be faced with an undesirable asset.

-

Interrelationship with Estate Tax, Income Tax and Succession Planning

- In General

The use of family limited partnerships as a tool for asset protection planning is incidental to its use for estate tax, income tax and succession planning. Although beyond the scope of this outline, the benefits of family limited partnerships include, income shifting (primarily for children over 14), retention of control by senior family members and possible death tax savings through the use of valuation discounts. The valuation discounts may be unavailable upon death if the creator of the partnership retained control as a general partner until his or her death. This issue does not appear to be clearly addressed at this time. See: Mulligan and Braly, supra and Spero, Chapter 8. supra.

The use of family limited partnerships as a tool for asset protection planning is incidental to its use for estate tax, income tax and succession planning. Although beyond the scope of this outline, the benefits of family limited partnerships include, income shifting (primarily for children over 14), retention of control by senior family members and possible death tax savings through the use of valuation discounts. The valuation discounts may be unavailable upon death if the creator of the partnership retained control as a general partner until his or her death. This issue does not appear to be clearly addressed at this time. See: Mulligan and Braly, supra and Spero, Chapter 8. supra.

- Valuation Discounts

The Tax Court has rejected the attempt of the IRS to assert that family attribution principles should prevent discounting of gifted limited partnership interests. In general, most discounts for minority partnership interests seem to fall into the range of 20% to 50%. Knott v. Comm’r, T.C. memo. 1987-597; Harwood v. Comm’r, 82 T.C. 239 (1984).

In Moore v. Comm’r, T.C. Memo. 1991-546, the taxpayer argued for a 40% discount, and the IRS sought a 10% percent discount. The tax court concluded that a 35% discount should be allowed for a minority partnership interest. Most recently, in Rev. Rul. 93-12, 1993-7 IRB, the IRS held that a shareholder who makes a gift of a minority stock interest to a family member is not precluded from taking a minority discount for gift tax purposes, even though the family controlled the corporation before the gift. In Wheeler v. U.S. 96-1 USTC 60,226 (D.C. Tax, 1996) the court allowed a 10% minority discount and a 25% lack of marketability discount for 50% of the outstanding stock of a closely held company owned by the decedent. More recently, in Barudin Est. v. Cmm’r., T.C. Memo 1996-395 (8/26/96), the Tax Court accepted the estate’s valuation of the underlying partnership properties and allowed a valuation discount of 45% (19% minority discount and 26% lack of marketability discount). In such case, the partnership’s only significant assets were commercial real estate in a recessionary market, and the partnership was effectively controlled by a majority partner.

- Realty: Discounts generally ranging from 10% to 40% (but in one case as high as 60%) have been allowed for undivided fractional interests in real estate (even if the other co-owners are related to the decedent). Some of the factors considered by the Courts include:

- The size of the fractional undivided interest involved. The smaller the fractional interest, the higher the discount;

- The number of owners of the real estate. Where there are fewer owners the discounts generally are less;

- The size of the parcel of real property and whether it would be practical to partition it, and at what cost;

- The availability of financing for the purchase of an undivided interest.

- Closely Held Corporations and Partnerships: Courts have generally allowed separate discounts for lack of marketability and minority interests for closely held businesses. Several leading cases have held that family attribution should be disregarded in valuing shares even where the “family” controls a business. These cases adopt a willing hypothetical seller/buyer test. See Estate of Bright 658 F.2d 999 (CA-5, 1981), Estate of Andrews79 T.C. 938 (1982) and Propostra 680 F.2d 1248 (CA-9, 1982). In 1987, tax legislation was proposed which generally would have eliminated a minority discount unless the entire family was in a minority position. The proposal was not enacted. Then in 1993 the IRS issued Rev. Rul. 93-12, 1993-1 CB 202 agreeing with Bright and Propostra.

- Planning: Creating minority discounts in closely held businesses can provide substantial estate and gift tax planning. If Dad dies owning one hundred (100%) percent of the family corporation, the estate tax valuation will be based on the value of the business without discount for minority ownership. However, if Dad during his lifetime begins making gifts to his children and grandchildren (or in Trusts for their benefit), a discount should be taken when valuing the gifted “minority interests”. Further, if Dad does not control the business at his death, minority discounts also should be available to value his remaining shares. What would a hypothetical unrelatedparty pay for a two (2%) percent interest in a family controlled corporation. A minority discount as well as a lack of marketability discount should be permissible.

Planning ahead is essential. In Estate of Murphy v. Comm., 60 T.C.M. 645 (1990) the decedent owned 51.41% of the stock of a closely held corporation. Eighteen days before his death, the decedent transferred shares representing 1.76% of the corporation, leaving 49.65% in the decedent’s estate. The Estate claimed a minority discount which the IRS disallowed. The Tax Court held that the transfer should be ignored for valuation purposes and denied a minority discount. The Court stated “the rationale for allowing a minority discount does not apply because the decedent and her children continuously exercised control powers” and “a minority discount should not be applied if the explicit purpose and effect of fragmenting the control block of stock was solely to reduce federal tax”. A similar situation to that of the Murphy case was before the Tax Court in Estate of Anthony Frank Sr., 69 TCM 2255 (1995). In Frank, the decedent owned 252 shares of a closely held corporation that had 501 outstanding shares. The other shareholders were his wife, two sons and daughter. Anthony’s shares were in a revocable trust. One of his sons was a trustee of the trust. Two days before Anthony’s death his son, acting pursuant to a power of attorney, removed 91 shares from his fathers trust, put them in his father’s name and then gifted them to his mother. The IRS took the position that the stock should be included in Anthony’s estate. The court rejected the IRS’ position and held that the son acted in accordance with his powers to remove the stock from the trust and convey it to his mother. The assets of the company were valued at almost $5 million and the court allowed a 30% lack of marketability discount and a 20% minority discount resulting in overall discounts of approximately 45%.

The trend is to permit larger discounts. See Scanlan Estate v. Comm’r. TC Memo 1996-331 (7/24/96) where the court allowed a 30% discount from the actual price stock was sold at 9 months after the decedent’s estate tax return was filed to reflect: passage of time; change in market conditions; marketability discount and minority discount. Even though a redemption of decedent’s stock occurred 2 years after decedent’s date of death, the court stated the redemption price was the best available evidence of the stocks’ value. Accordingly, the court applied the above-mentioned 30% discount to the actual redemption price recovered just 2 years after the decedent’s date of death.

The trend is to permit larger discounts. See Scanlan Estate v. Comm’r. TC Memo 1996-331 (7/24/96) where the court allowed a 30% discount from the actual price stock was sold at 9 months after the decedent’s estate tax return was filed to reflect: passage of time; change in market conditions; marketability discount and minority discount. Even though a redemption of decedent’s stock occurred 2 years after decedent’s date of death, the court stated the redemption price was the best available evidence of the stocks’ value. Accordingly, the court applied the above-mentioned 30% discount to the actual redemption price recovered just 2 years after the decedent’s date of death.

Fractional discounts allowed for interests in the same property owned by QTIP Trust and Surviving Spouse. In Bonner Estate v. U.S. No. 95-20895, 5th Cir. (6/4/96) the court rejected the IRS’ argument that when valuing a property owned in part by a surviving spouse outright and in part by a Marital Deduction QTIP Trust created for the surviving spouse that the interests should be combined . In Bonner the decedent owned a 62.5% interest in a ranch. The remaining 37.5% was owned by a QTIP Trust created by the taxpayer’s spouse. The estate claimed a 45% discount (below 62.5% of the fair market value). The court held that the estate was entitled to a fractional interest discount for the property and remanded the case for the appropriate discount. The court said that the position of the IRS is “not supported by precedent or logic”. The court said the appropriate test is that of a willing buyer and willing seller. The court said each decedent should be required to pay tax on those assets whose disposition the decedent directs. In the case of the QTIP assets, the court stated the spouse who established the QTIP Trust had control, not the surviving spouse. Note: The Bonner decision is contrary to TAM 9608001 where the IRS held that with facts similar to Bonner, QTIP Trust property should be valued as if it was owned outright by the surviving spouse.

- Stepped Up Basis

To the extent that a donor is unable to completely give away his interest in property prior to death, he would like to make certain that his retained interest receives a stepped-up basis to its fair market value under IRC Section 1014. In the partnership context, the estate of the donor/partner can request that the partnership elect under IRC Section 754, to increase the deceased donor/partners basis in his share of the underlying assets of the partnership to fair market value at the time of death.

- Family Partnership Rules

Most family limited partnerships created for asset protection purposes will have significant capital and, therefore, IRC Section 704(e) will apply to support allocations of income to partners who received their interests through gifts. Nevertheless, the regulations under IRC Section 704(e) should be followed to insure that a partner will be considered a true partner.

- Investment Company Rules

It should be borne in mind that the general nonrecognition rule under IRC Section 721(a) concerning contributions of appreciated assets to a partnership does not apply to gain realized upon the contribution of property to a partnership which would be considered an investment company under IRC Section 351 if such partnership were a corporation. However, it appears that where one family member contributes the bulk of the assets to a family limited partnership (and the transfer does not result in diversifying such family member’s security investments) the investment company rules should not apply.

The Public Interest Law Center renders legal services mainly to organized sectors of Philippine society on legal issues that have a direct or indirect impact on the lives of numerous classes. As a principal mission, PILC is committed towards fighting for actual, tangible, and quantifiable gains for its clients. On a supportive role, PILC realizes that its legal advocacy and battles inspire and promote the organization of the poor and oppressed and their conscientization towards fighting injustice and

oppression.

The scope of PILC services ranges from legal services, education and training, advocacy, consultancy, legal research and library services. As a front line advocacy group, PILC is directly engaged in litigation, legal consultancy, and the legal audit of organizations and institutions as part of the scope of its legal services.

The PILC believes that it should exert every effort to translate legal victories and struggles into tangible gains for its clientele. In a way, PILC seeks to move human rights into the mainstream of public consciousness by disabusing the concept of its highly political connotation. By using public interest law as an effective instrument in seeking economic and social relief, reform and change, PILC champions not only the cause of human rights but the right to development of its clientele.

PILC IS GUIDED BY THE FOLLOWING PRINCIPLES IN THE HANDLING OF PUBLIC INTEREST CASES:

1. The issues fundamentally affect the lives of a large number of people usually a sector of society or even the whole society itself.

2. The issues arose out of a conflict of rights or interests and exploitation and oppression of the numerous poor by the tiny privileged sector and/or government policy or program.

3. Unlike the traditional practitioner, the public interest lawyer views and handles the legal issue and the case in the larger context of the nature and problems of our society.

4. Having accepted the professional responsibility to handle the public interest case, the lawyer initiates and assists in a process whereby the public interest issue and the legal battle are utilized for organizing, and raising the social awareness, unity and militance of the clients and other who support the cause of the clients,

5. The legal battle is not confined to the courtroom. The Public interest lawyer uses what the great lawyer, the late Jose W. Diokno calls meta-legal tactics, mobilizing and utilizing the clients’ strength, unity and militance, bringing the issues to the public, and rallying support for the clients’ cause.

6. In the handling of the case, the public interest lawyer interacts with his clients in the mutually beneficial way whereby he or she learns and deepens his or her commitment to the clients’ struggle for the empowerment and betterment of their live. The relationship is broadened from a mere professional one to a unity of understanding of the problems of Philippine society and common goals for fundamental reforms.